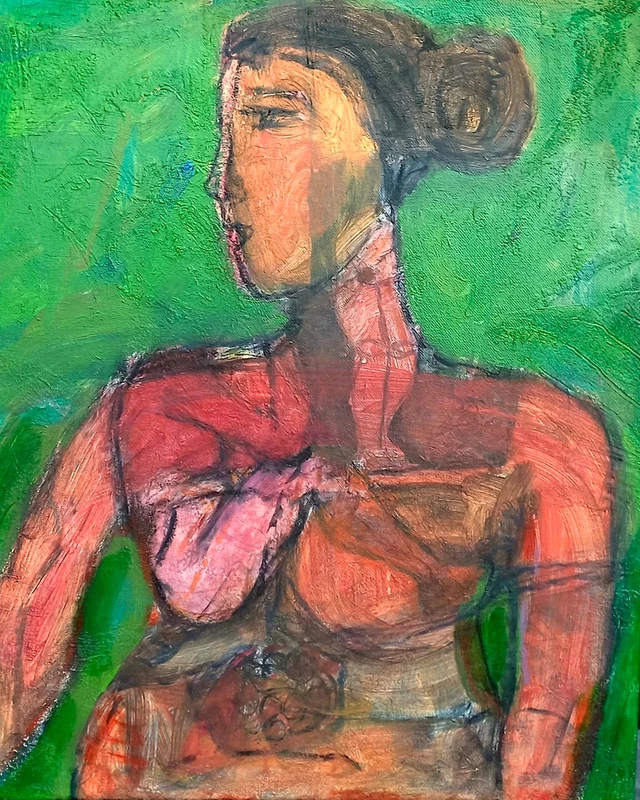

Margaret Hunter: States of Being

7 Sep-29 Sep 2023

Paintings on board and canvas range in scale from 100 x 70cm to the small group of 18 x 24cm pieces, accompanied by powerful A2 drawings in charcoal and pastel. There is also a beguiling ceramic sculpture, The Glindow Girl. Perhaps the more reflective note in these recent works originates from the Covid-19 lockdown period when Hunter worked on her archive, sifting through and re-visiting ideas that had evolved over decades, and then she travelled to Malaga where an encounter with the Picasso Museum inspired a new departure.

Something she feels strongly about, and which has had an influence on her practice for many years, is the expansive wall painting, Joint Venture, which she made on the longest remaining part of the Berlin Wall left standing in 1990. It is now called the East Side Gallery and it was painted on by 118 exuberant international artists. Hunter signed her name with ‘SCOTLAND’ in bold letters. Today, the East Side Gallery has memorial status and with four million visitors a year, it is one of the major attractions in Berlin.

In her own words, here is the remarkable story behind her successful career:

I was 33 years old, newly divorced and with two children when I started my study at the Glasgow School of Art in 1981. This was a second chance in life. Painting and drawing every day, having access to mountains of art books in the library and discussing ideas with other students made it one of the most challenging but rewarding periods of my life.

It was on an art school trip to Amsterdam that I first saw the work of Georg Baselitz in a huge retrospective exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum. The powerful combination of vibrant strong colours, simple direct compositions based mainly on the single figure, was overwhelming. I tracked down his address and rather naively wrote him a card saying how much I’d enjoyed seeing his work. To my surprise, he responded and later accepted my request to study with him for a year.

After securing financial support and family arrangements for my children, I arrived alone in Berlin. But my euphoria was short lived: I didn’t know anyone and could hardly speak the language. For the first time in my life, I was really alone with no family, friends or contacts in this new city - it is at times like these that you are completely thrown back upon yourself. Mainly I observed and I noticed what was going on around me, particularly peoples’ gestures.

Dr Sandy Moffat (formerly Glasgow School of Art) observed that Hunter’s works “not only confront the precariousness of our times but assert human values above all else.”

One of the most important pieces of advice Baselitz gave me was that I should draw draw draw to clarify my ideas. To this day I always make small initial drawings and sketches, expressions of free imagination and inventive mark-making which give birth to the ideas for larger paintings and sculptures. Through drawing incessantly without inhibition, I devised new pictorial metaphors, often using animal symbols, like the snail carrying its house on its back which I felt was very relevant to my own situation. The barbs sometimes surrounding a figure in those days was an allusion not only to the barbed wire surrounding the then divided city but also to personal borders and limitations. I made drawings that would not have been possible in Scotland and without fluency in the German language they became my main means of expression.

The tumultuous history and the exciting yet edgy atmosphere of Berlin became almost more of an influence than Baselitz. Impressions and realisations came at me from all sides as I experienced a cosmopolitan half city which sat like a glittering island in the middle of East Germany. No matter where you went in West Berlin at that time you always came up against the Wall. Reinforced on the eastern side with barbed wire were ’death strip’ mine-fields and armed guards on watchtowers.

I vividly remember the first visit I made to East Berlin in 1986; it was like moving from thriving opulence and colour to the dust and greyness of potholed roads, crumbling buildings, and an overwhelming feeling of drabness. This division of Berlin with its dual identity paralleled my own life split between family in Scotland and life in Berlin, commuting between the two for months at a time.

Certain themes, like duality in relationship to the human condition, are a recurring interest; the duality of the emotional and physical self; individual and collective identity; the relationship between two people. Duality is often depicted as two heads or figures whereas the mask refers to an individual person, alluding to their inner life.

Art critic and writer, Susan Mansfield, put it this way in 2017: “Her works are about the human figure, but they are also about humanity, about how we accept duality, whether that of self and other, or those dualities which are contained within ourselves.”

Hunter’s sculptures have a special affinity with African art. It was during an interview with Susan Loppert for an article in the Contemporary Art Magazine where she suggested that Baselitz, with his extensive collection of traditional African artefacts, might have been a stepping-stone back to memories and impressions Hunter had from a childhood period spent in Nigeria with her family.

She concentrates mostly on the single figure which is stylised, reduced to the vital and essential and generally, the female form. This has been Hunter’s main subject as the carrier of meaning. The figures themselves are inventions, not drawn from life. Their movement, gestures, poses, form a distinctive choreography of well-being, or as the title of this exhibition has it, States of Being.

Symbolic forms that matter to her are repeated; these are her personal language. Usually there is some form or object attaching the figure to its world, giving it a sense of belonging. She knows the origins of each of these symbolic forms - the moment of discovery, and their gradual, significant evolution.

Angela Weight commented in 2006 that “an oblique, abstracted language such as hers holds us at a distance at the same time as it fascinates and intrigues, endlessly provoking imaginative speculation.” Hunter’s paintings are generally made up of complex layers of paint where the process of over-painting invests the work with a history. It also allows her to scratch back into the painting, to physically uncover in order to build up and reveal parts of the painting’s other life beneath the surface.

This probing parallels her method of allowing subconscious material to surface, transforming earlier experiences and impressions into tangible ideas. The tension between the two ways of working and thinking, intuitive and intellectual, is embedded to build an energy and an inner strength that has been characteristic of her art from the outset. It reflects the artist herself and her extraordinary, resolute journey from Fairlie on Scotland’s West Coast to the international dynamism of Berlin and an impressive career that unfolded in Scotland, Germany and in London.