Johan Creten: Far removed from the numbing speed

14 Nov-20 Dec 2024

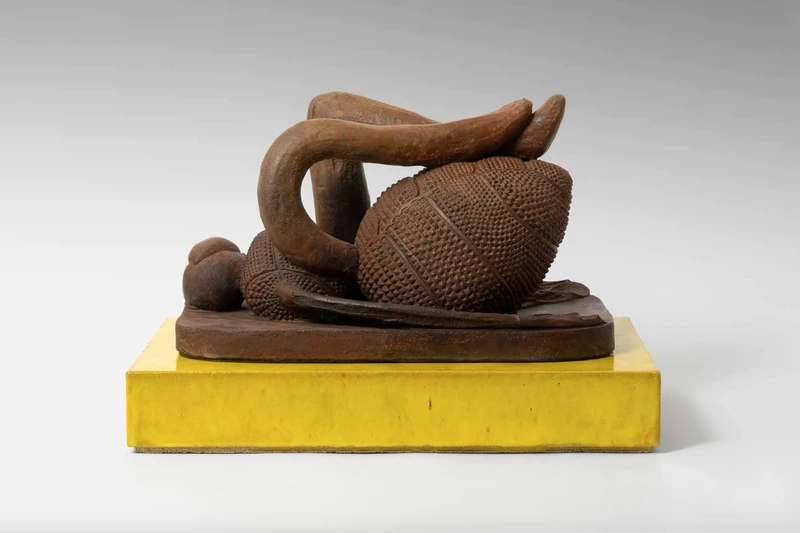

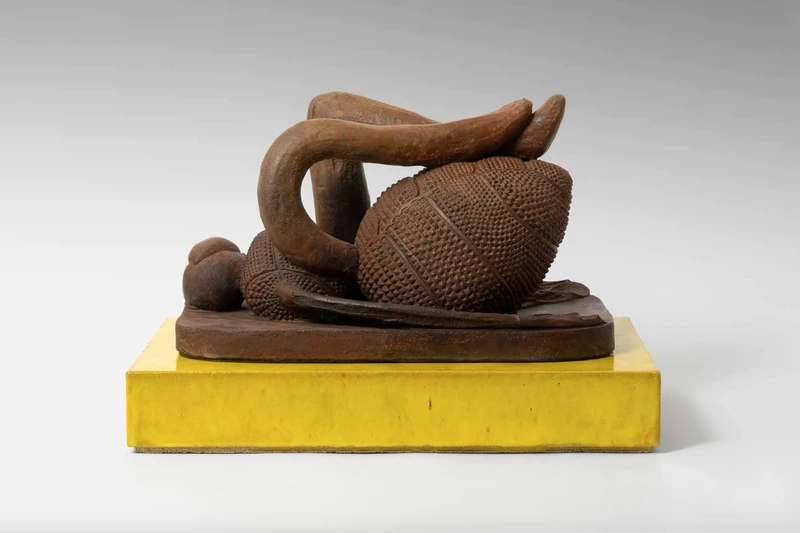

Almine Rech is delighted to present “Johan Creten: Far removed from the numbing speed”, a more intimate approach to the artist's work with a set of sculptures he calls “library versions”. These pieces, of a size close to the clay models produced before his monumental works—like the Renaissance traditional bronzes that he collects, are designed for the home: to be placed on a desk or nestled between books. As the title's formula ironically suggests, the aim of this exhibition is to pull us out of modern life's saturated pace and digital over-consumption by giving us a more engaging and regenerative personal art experience.

Despite his international success, the Belgian sculptor's work has rarely been shown in Great Britain. In 2005, Odore di Femmina, his porcelain torso, was exhibited in the setting of the Wallace Collection, in a dialog with a collection ranging from the Middle-Ages to the 19th century. In 2010, his half-human half-fruit creature Why Does Strange Fruit Always Look So Sweet? harmoniously blended in the Victorian surrounding of Chatsworth House's Rock Garden. The masterly encounter between these works, which are emblematic of his contemporary ceramic practice, and monuments of British heritage has nevertheless highlighted the “timeless” relationship they have with the past. This blurring of time and spatial reference points builds clear bridges with Symbolism, a movement that sought to create situations of introspective ruptures with the turpitudes of its time, by lyrically plunging us into an elusive time between an old ideal and the construction of a world to come.

This London event follows on from the exhibition “How to explain sculptures to an Influencer?”, when the artworks were first shown. While adding a difference in patina, Johan Creten uses the stage principle of the Parisian installation: on a wooden platform, small bronzes shaped with lost-wax, based on the artist's “bestiary”, including Sauterelle, l’Hippocampe, Mouche morte, l’Hypocrite, and Mouton, as well as mythical figures such as Femme au hareng, are grouped together. A “mural décor” made up of the bas-reliefs La Rencontre and C’est dans ma nature, as well as Miroirs d’argent amplify the composition's narrative character. The panoramic view of the whole can be appreciated from the glazed stoneware plinth-sculptures, which he aptly entitled Points d’observation.

This set-up is reminiscent of the “Gesamtkunstwerk” concept, a fully integrated artwork that dissolves the boundaries between art and life. Furthermore, the narratives that result from this unusual confrontation between the artist's mythological creatures—the large versions of which are found at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris, exhibited at the Musée d’Orléans in France, or along the Flemish coast—go beyond the theatrical framework of the animal fable or the commedia dell'arte, delving closer to the depths of Wagnerian dramaturgy. The soothing and contemplative atmosphere that emanates contrasts with the pace of our modern lives, marked by the crushing weight of social media and the excessive abundance of images and information. In the face of “numbing” effects of this overconsumption, the exhibition reveals the artworks' introspective as well as revitalizing power. Johan Creten says: “Each sculpture is an enigma that can be interpreted as a memento mori or as a codified reflection on the vital force of life, endowed with a truly remarkable inner strength.”

Henry Moore, who has influenced the Flemish artist with the monumentality of his work between abstraction and figuration, as well as with his shapes inspired by primitive cultures, established links between the origin of such a “vital force” and the basis of the “Gothic ideal”, a structure element in Johan Creten's allegorical imagery: Unlike the “Greek ideal”, this beauty stands out for the “power of its expression” triggering “a spiritual vitality … that goes beyond our senses … that may be in direct contact with reality; … that perhaps expresses the very meaning of life and arouses a great desire for life.” By virtue of this spiritual consistency, he states that “monumentality is a mental thing”: “The grandeur of a shape comes from the quality of its vision rather than from its physical dimensions. This quality is spiritual in essence, which is why … even tiny sculptures may have this grand presence.”

It may seem appropriate to associate the introspective depth of Johan Creten's creations with a “sacred” experience, as this aspect of his work has been widely recognized, whether through his choice of existential themes, the ancestral materiality of his practice, or the anthropomorphic shapes of his sculptures, inspired by religious or symbolic iconography. Additionally, the Wagnerian character of his stagings reinforces this sacredness. This statement opens up a new avenue by re-contextualizing the artist's productions in the domestic environment. In his book The Sacred and the Profane, Mircea Eliade stresses the transformative power of the sacred in the everyday life of traditional societies. Sacred myths allowed people to return symbolically to the mythical time of the origins, to the moment when the sacred structured the world. This return to the origins allowed the individual or the community to regenerate themselves.

In the continuity of the objects he collects, said to be rooted in the old, or even archaic, imagination, Johan Creten injects, with this set of sculptures, a dose of “sacredness” into our mundane lives. By offering us lyrical interludes that reconnect us to the reality of a universal “Whole”, these works restore an existential meaning into the emptiness of the everyday, disorientated by its hyper-connection to the social media's “virtual” theatre. In these times of turmoil and disillusionment, their depth inspires us, day after day, with the creative energy we need to transform ourselves. Did Baudelaire not see in the Symbolist dream of Wagnerian operas “the index of modernity”, in other words, the advent of a new world?

— David Herman, artistic director and curator