Marlene Dumas: Mourning Marsyas

20 Sep-16 Nov 2024

PV 19 Sep 2024, 6-8pm

The paintings in this show are created through a mixture of chance and intention, mostly evolving in a dance through time, combining very fast and focused actions with reflective pauses. Here, Dumas’s style as well as subjects move between being in and out of control. We encounter neither portraits nor observations, but images of feelings and moods. The tone is one of mourning, of the desperation of displacement, and of grief both personal and universal.

For the artist these sentiments find their expression in one of the great and ancient parables. In Book Six of Metamorphoses, Ovid recounts the story of the satyr Marsyas, who challenged the god Apollo to a musical competition. In the contest (which was judged by the Muses), the terms stated that the winner could treat the loser any way they wished. Apollo triumphed and he punished his challenger by skinning him alive. Dumas relates to the version that says Apollo won by the trick of playing his lyre upside down, while Marsyas’s flute could not be played that way. To her, Apollo represents unjust revenge, and Marsyas symbolises not excessive self-belief, but rather liberty and artistic freedom, speaking truth to power.

Even before she read about the story with its various interpretations, Dumas was inspired and moved by a photograph of a Roman statue in the Louvre depicting Marsyas stretched-out and tied to a stake. She admired the wildness of the satyr daring to challenge a god who maintains power by any means necessary, tracing parallels with our present political leaders, who rule not by joy and justice but by addiction to power. Ancient atrocities and massacres seem to duplicate themselves in the present.

Dumas’s large painting Mourning Marsyas (2024) has grown organically. Like several other works in the exhibition, it began with paint poured directly onto the skin-like canvas. From this elongated stain, a central figure has been teased out, with others painted beside and around it.

Fortune (2024) is a painting equal in height but even larger in scale, its title is after a drawing by Albrecht Dürer. In this work, a combination of poured and worked paint has produced an intriguing image from which three distinct forms emerge and interact yet remain very separate. These strange characters might be more animal than human, their surfaces and voids created by effects of brush strokes and areas of drying paint. They are a mixture between figuration and emptiness, effortlessness and struggle. Another work, Two Gods (2021), has materialised in a similar way, becoming an image of a pair of monumental phalluses.

In The Widow (2021-2024), a dark figure looms out of the shadows. Its head is skull-like, and the lower half is obscured, perhaps by a veil. Created over several years, this figure was made for the Dutch translation of Charles Baudelaire’s Le Spleen de Paris by Hafid Bouazza, to illustrate the prose poem XIII, “Widows.” It followed Dumas’s exhibition Le Spleen de Paris at the Musée d’Orsay (Paris) in 2022, which celebrated the bicentennial of Baudelaire’s birth. Dumas also sought to express her own widow-like emotions following several deaths in her private life.

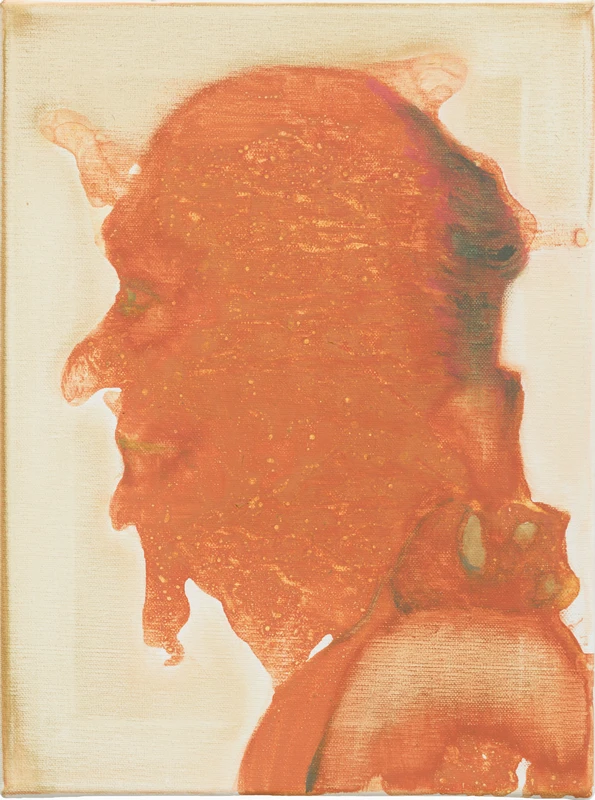

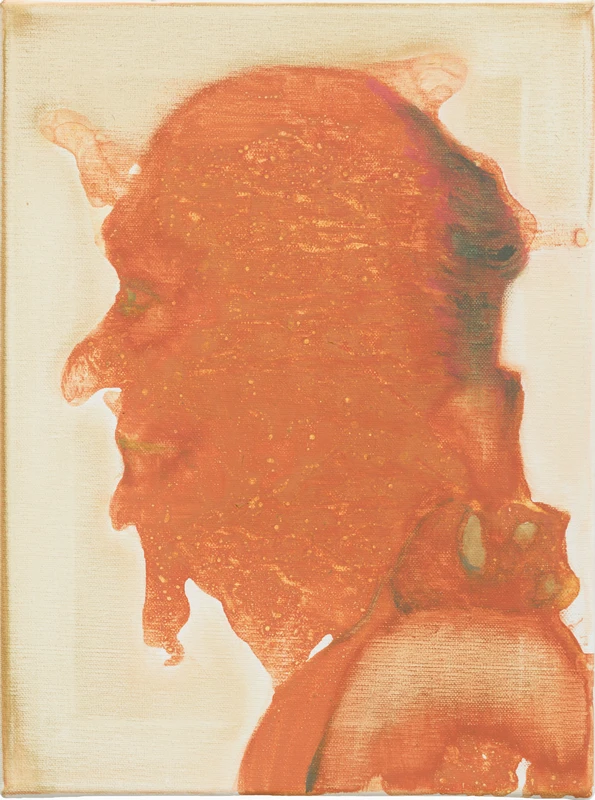

When discussing some of the paintings in the exhibition, Dumas uses the term ‘Pareidolia’, which describes the tendency to perceive specific, often meaningful images in an ambiguous visual pattern – an ability to see shapes or make pictures out of randomness. The term applies to several faces and figures in this show that have evolved from poured areas of paint. One such face, a particularly bloated visage with unsettling rudimentary features is itself entitled Pareidolia (2024).

The small work Fate (2000-2024) emerged over many years, eventually becoming a quietly perturbing image of a skeletal, crouching, almost insect-like figure. A central concern in Dumas’s practice has always been how to create a sensual work about the inescapable fact of death. She explains that one of Francisco de Goya’s black paintings, Atropos, (The Fates) played a part in its conception:

“Then I walked into the room with Goya’s black paintings, they put their spell on me. I covered my mouth as if to prevent the devil from entering. The Fates does away with the abstraction versus figuration discussion. Everything is flat and deep simultaneously. The four sexually ill-defined figures are unsympathetic. They are forces, not human beings.”