Where Can We Live But Days?

28 Jun-10 Aug 2024

Mamoth is delighted to announce Where Can We Live But Days?, a group exhibition of eight international artists, which meditates on how we navigate – and conceptualise – our passage through time and space.

Where Can We Live But Days? takes its title from a line in Philip Larkin’s poem ‘Days’ (1953). Larkin was, of course, asking a rhetorical question. As the work of the artists in the exhibition demonstrates, we are temporal creatures, fated to exist in a remembered past, an always-receding present and a future we might anticipate with hope or fear, but whose contours we will never quite know until it at last arrives. Days are where we live, and where we create – and recreate – our understanding of ourselves and of our world.

Nicholas Campbell (b.1995, lives and works in Los Angeles)

If the recent, abstract canvases of Nicholas Campbell recall the walls of deep, subterranean caverns, of the kind on which our distant, palaeolithic ancestors created the first art, then they also resemble a malfunctioning digital screen. Employing smashed silver leaf, metallic paint and smudges of greasy, bruised-looking pigment, Campbell offers up more visual information than we could possibly digest, a decadent feast of data for an age of excess. The artist provides us with no instructions as to how we might assimilate these works. Instead, we are left to sink or swim, to glide over their reflective surfaces, or plumb their dark and treacherous depths.

Henry Curchod (b.1992, Palo Alto, CA, lives and works in London)

Disquiet – both social and existential – is perhaps the dominant atmosphere in Henry Curchod’s paintings, which toggle between expressionism and an almost cartoonish register with considerable aplomb. The everyday figures he depicts are often caught up in moments of conflict or humiliation, or else appear to be suffering some physical or psychological collapse, although the reasons for this are rarely, if ever, clear. Perhaps it is simply that we live in an angry, impossible age. The artist’s use of oil stick gives his work an urgent, almost documentary quality, as though he was attempting to transcribe these scenes from life, before their details fade from memory, and with them our sympathies.

Beaux Mendes (b.1987, New York, lives and works in Los Angeles)

Beaux Mendes is both a painter and a pilgrim, whose practice sees them visit remote, often obscure sites to work on their canvases en plein air. Place, in these images, is not so much depicted as channelled, first through the artist’s mind and body, and then through their pigment as it meets the support. Mendes has said, ‘My paintings contain a double negative: the surface works to undo itself and representation is obscured to reveal a subject that is not an image of the past, but an impression directly inscribed in it.’ What is captured here is an encounter with location, in which spatial and temporal boundaries are dissolved in the artist’s restless paint.

Elizabeth Peyton (b.1965, Danbury, CT, lives and works in New York)

Elizabeth Peyton’s intimate, unabashedly romantic portrait paintings depict figures as diverse as the musician Kurt Cobain, the activist Greta Thunberg and the nineteenth-century Bavarian monarch King Ludwig II. What unites her oeuvre is the way Peyton imbues her subjects with a delicate physical beauty, and a disarming mixture of vulnerability and poise. If these works are concerned with the creation of a personal pantheon of icons, and the tracing of a shared sensibility across time and space, then they also focus on how a public persona shapes a private self, and on the inexorable transience of fame, desire and youth.

Amedeo Polazzo (b.1988, Starnberg, Germany, lives and works in London)

An artist preoccupied with ephemerality and permanence, Amedeo Polazzo creates murals using the fresco-secco technique, which are designed to be temporary, and works on canvas, which are designed to endure. In each case, the motifs he paints feel like objects glimpsed in a dream, or fragments of some half-forgotten memory. Humming with latent meaning, but refusing to offer up a linear narrative, these are images that ask us to reflect on our lifelong, apparently ever-forward journey through time. Notably, Polazzo arrives at his finished canvases by gradually building up and erasing layers of pigment, tempera and oil. What is lost during this process is perhaps as significant as that which remains.

Fabian Ramírez (b.1994, Mexico City, lives and works between London and Vienna)

Rooted in the histories of the Indigenous peoples of Mexico and their complex relationship with Catholicism, the works of Fabian Ramírez are a riotous testament to the physical and spiritual violence of colonialism, and to how embattled cultures resist and endure. Employing a traditional encaustic technique known as hot wax painting, he creates heady visions alive with gods, monsters and writhing human figures, licked with flames and great waves of colour. Acts of creation and destruction blur into each other, pre-Hispanic symbolism combines with Christian iconography, and new forms spring from the scorched earth.

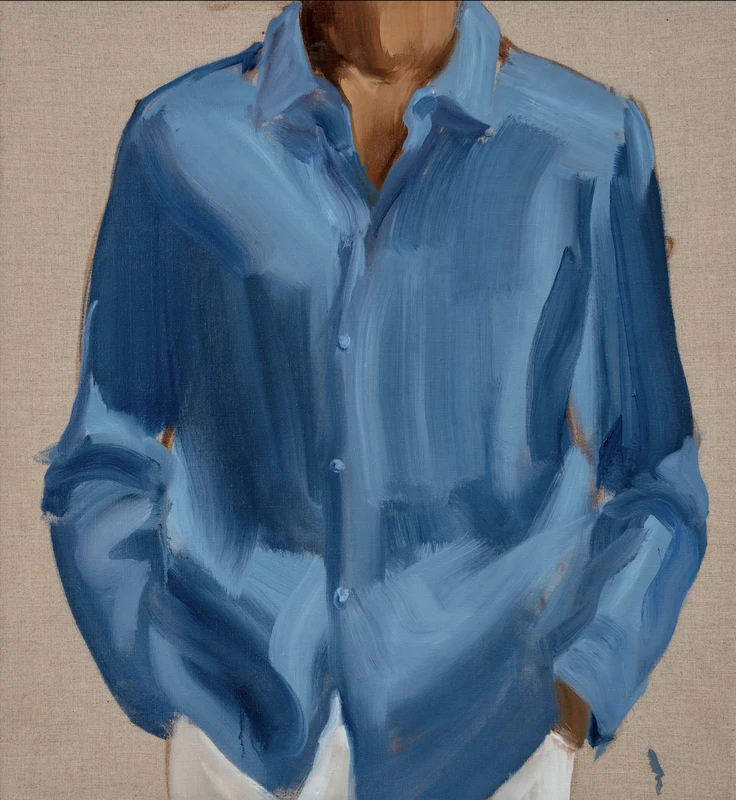

Gideon Rubin (b.1973, Tel Aviv, lives and works in London)

While the people depicted in Gideon Rubin’s paintings have blank ovals of pigment in place of facial features, their essential humanity – and indeed, their individuality – is never in doubt. Often derived from vintage photographs, or works by Old Masters, these images demand that we focus on poses, atmospheres and above all on the artist’s spare yet sensuous application of paint to his raw linen, canvas and board supports. The economy of Rubin’s approach allows space for us to enter his still and muted painted worlds, to experience them almost as though they were forgotten episodes from our own pasts, rising up through the fog of memory.

Wilhelm Sasnal (b.1972, Tarnów, Poland, lives and works in Kraków, Poland)

‘My mind is incapable of producing fiction,’ says Wilhelm Sasnal, ‘I always try to draw on things that already exist.’ The Polish painter’s reference points are often other images, whether these are innocuous snapshots of friends and family, or stills from Claude Lanzmann’s devastating Holocaust documentary Shoah (1985). The common thread in his work is not its subject matter, or indeed its style or technique, which can shift with great deftness from canvas to canvas. Rather, what persists is Sasnal’s laconic tone, and his innate distrust in the adequacy of images to represent reality.

Text by Tom Morton