Kimathi Donkor: Black History Painting

15 Mar-20 Apr 2024

In his new exhibition 'Black History Painting' Kimathi Donkor continues his ongoing re-centering of black historical figures who have been ignored by mainstream western history or are victims of police and state brutality. He references and uses the tools of the genre of history painting, evoking that visual language to actively difference the canon. Donkor has been working in this way since the early 2000s, and these works can be seen as prefiguring more recent debates in both art history and wider society. In particular Donkor's way of working has a strong parallel with the academic Saidiya Hartman's idea of 'critical fabulation' a way of working that Hartman says "troubles the line between history and imagination."

The notion of critical fabulation is a strategy that produces a counter-history of black subjects who were enslaved, fought against slavery or were subject to more contemporary forms of oppression. It adds to gaps where conventional history in the form of archives or written testimonies are scarce or contested. In this way these black subjects are given a fuller agency. These are images that are rooted in whatever historical record is left but re-think the archive through imagined moments and futures. Donkor has been working in this way since the early 2000s with works that featured figures including Toussaint L'Ouverture, the leader of the Haitian Revolution against its French colonial occupiers and the Nanny of the Maroons, who lead a community of former slaves in a guerrilla war against the British authorities in Jamaica.

Central to Donkor's works is not simply re-inserting these overlooked figures into contemporary discourse, but simultaneously critiquing the art historical genre of history painting. Donkor does this by clearly nodding at that style of painting but also by very specifically referencing particular works. So for example, 'Nanny of the Maroons' Fifth Act of Mercy' (2012) (currently on view at the National Portrait Gallery) visually echoes Joshua Reynold's painting 'Jane Fleming, Later Countess of Harrington' (1778), which was a portrait of a British aristocrat whose family was involved in enslaving people in Jamaican plantations.

Donkor uses historical records, imaginative speculation and the language of history painting to suggest what a broader concept of the genre could be, one that addresses history from a rounded perspective rather than through solely a colonialist gaze. In his new exhibition at Niru Ratnam, Donkor will present two new major paintings that continue this ongoing project. He will also present one older work from 2014 as well as two major paintings that were shown at the Sharjah Biennial (2023), accompanying works on paper and a film work.

'The Miraculous Destiny of James Somerset' (2024) takes the figure who was at the centre of one the most celebrated court cases of Abolitionist history in England. Somerset was a West African-born slave who left his slave-master in London, Charles Stewart. The ensuing court case brought by Stewart to retrieve what he argued was his 'property', was dismissed by the Chief Justice of the King's Bench and widely interpreted to signal that slavery was illegal in England and Somerset was a free man. However there are no records of what subsequently happened to Somerset; in this new work Donkor imagines the former slave's future as we see him posed defiantly outside a modest house with his family in what might be an English village or town.

In a second new painting 'Mary Prince Dictating to Susanna Strickland' (2023) Donkor pictures the escaped slave Mary Prince who re-told her biography to the writer Susanna Strickland resulting in the first published account of slavery by a black woman 'The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave, Related by Herself'. In this painting we see Mary Prince as what she became after freeing herself from slavery; a story-teller, an abolitionist and a rebel. The painting is exhibited alongside a diptych showing two different stages of Prince's life, the first as a child at the mercy of her slave-mistress, and the second retelling her story later in life to an astonished Strickland.

Alongside these two major new works the exhibition will feature paintings seen for the first time in London as well as works on paper. In the 2014 work 'Maria Firmina Dos Reis reads to Henry Tate; Luís Gama, Donald Rodney and Isabel Bragranza confer', Donkor draws on his own research around the origins of Henry Tate's family wealth. Along with Tate, who poses nymph-like, we see a group of figures from disparate times in history brought together to interrogate the origins of the trade that provided the foundations of Tate's own wealth from Liverpool's sugar industry. Gama and Braganza were both Brazilian abolitionists, their presence highlighting the role that Brazilian slave-produced sugar played in Liverpool's sugar industry. Rodney was an artist who as part of the Black Art movement in the 1980s proposed an unrealised work re-constructing Tate's Millbank site out of sugar cubes. Meanwhile, Maria Firmina dos Reis reads to Tate, and it is not unreasonable to imagine she reads from her own book, 'Ursula' that documented the lives of enslaved Brazilians.

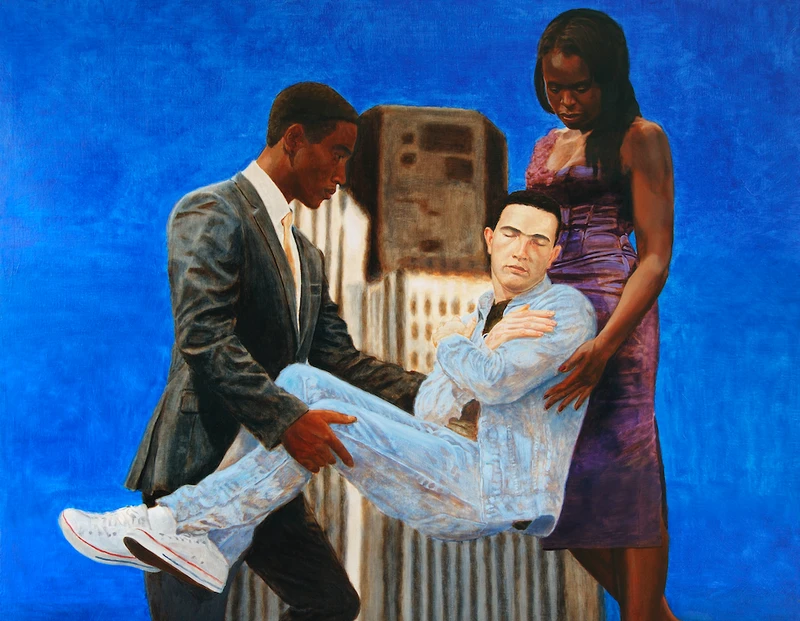

Two other paintings in the exhibition use the language of history painting to show scenes that have their starting point as police racism and brutality in Britain. 'Jean Charles Menenzes Borne Aloft by Joy Gardner and Stephen Lawrence' (2010) and 'The Death of Clinton McCurbin' (2023). These works continue Donkor's memorialisation of subjects who have died at the hands of either the police or through racist violence in the UK. In both these paintings Donkor portrays these figures as suspended, floating in the area around them. In the former the three figures are seemingly weightless. As Donkor described: "The trio seemed, instead, to defy forces that were perhaps far more unrelenting and remorseless - without wishing to sound pretentious, I mean such forces as myth, power and mortality. Perhaps even nature itself, in the form of gravity." In the more recent painting, 'The Death of Clinton McCurbin' the three figures pin McCurbin down with a horrific urgency, mitigating against the freedom of space that the figures in the earlier painting have.

Both these works tie into a final theme in the exhibition, that of bearing witness. The film '439 New Cross Road' (2015) about the New Cross Fire that killed 13 young black people in 1981 is a meditation on the importance of bearing witness, what is remembered and what is forgotten. A work on paper 'Notebook XXV-V-MMXX' (2021) finishes the exhibition depicting a young woman on her phone, a new form of witnessing through its camera that points to a future where events do not fade. That work visually and conceptually echoes the work on paper 'T Ras Makonnen' (2023), an image of the now largely-forgotten pan-Africanist, philanthropist and entrepreneur who funded his Pan African Publishing Company through profits from restaurants he owned in Manchester.

At the same time as the exhibition at Niru Ratnam, Donkor will also be exhibiting in 'The Time Is Always Now: Artists Reframe the Black Figure' at the National Portrait Gallery, London as well as 'Soulscapes' at Dulwich Picture Gallery, London.