Oli Epp: SHAMPOO

13 May-27 May 2023

PV 13 May 2023, 6-8pm

Carl Kostyál is delighted to present an exhibition of new paintings by London born and raised artist Oli Epp, his third with the gallery.

How to picture the human subject today? How, more specifically, to continue the longstanding project of painting people as they are in the artist’s era—and thus, today, represent body and mind as violently reshaped by twenty-first-century technocratic capitalism? You surely know how this feels, whether or not you’re old enough to remember a different, slower, less ferocious time. It feels like this: coercive. Extremely online (even before the pandemic), endlessly chivvied to self-optimise and self-brand, moving through a life stickered with advertising and logos and the corporatisation of everything, made hair-trigger aggressive by social media, lacking a functional attention span, beset by ‘treat brain’ and the desire for sugar or other stimulants or depressants, conditioned to be perpetually out for oneself, seduced by bright digital surfaces, trying futilely to be an influencer… one could go on. It’s rare to have not experienced this. It’s rarer still, however, for an artist to find representation of this mode of living, (which amounts to a social experiment), in succinct, original pictorial form.

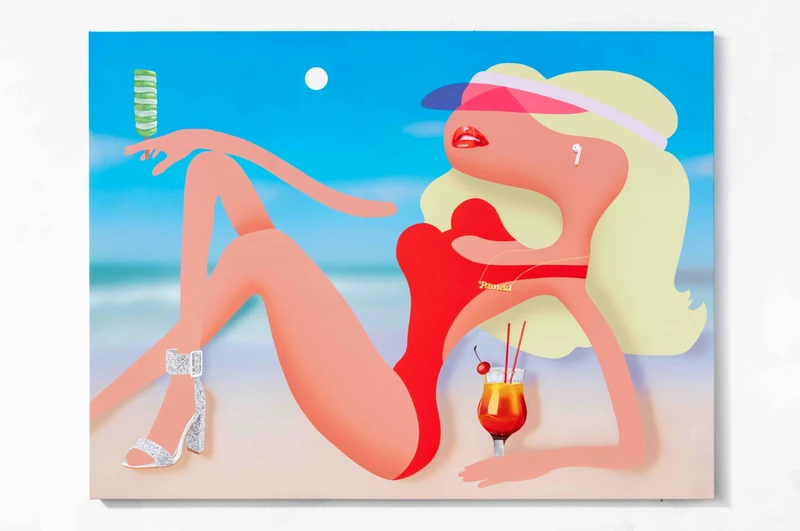

Oli Epp (b. 1994, London, UK) succeeds and without reducing his art to anything like illustration or sheer, weary social commentary. His paintings—begun as instinctive drawings, passing through Photoshop and then spun out in seductive yet unnerving canvases whose impeccably punchy compositions combine oil, acrylic and spray—pop vivaciously whether seen in person or onscreen. At first glance, they’re pleasurable things: typically, though not always, focused on a single figure (or, perhaps, entity), they have a cartoonish brightness about them and as the eye slides over their wipe-clean surfaces, smoothly gradated fields of colour and fluent bursts of Photorealism, they’re gratifying to look at. But all of this, it’s quickly apparent, serves as a counterweight to an abundant anxiety concerning what we are morphing into as a species.

His figures are mostly approximately human, for all that they typically don’t have eyes, so no windows to the soul and maybe not much soul either. Their big heads balloon to nearly fill his frames. They have cigarettes or pencils or pills where their ears should be, or they’re plugged with earbuds. They have realistic mouths, for all that they’re often vampiric, grasping, and somehow abject. This puts Epp’s paintings in conversation with Pop (indeed, he’s referred to his art as Post-Digital Pop, and one sees particular imprints of Tom Wesselmann and Allen Jones) and Epp is evidently pursuing the question of what a legitimate Pop art might look like today. His answer is that it must address the particular conditions of modern life outlined above, that it must engage the digital—but also, again, that it must be post-digital. It’s important to note that Epp’s artworks are physical, handmade things, replete with the hard-won pleasures of technique. It’s also important that he plants himself, and thus his viewer, strongly in the physical world.

This fact doesn’t end at his paintings. Epp is big on offline community and for the past four years he has run the migratory PLOP residency in London, giving international artists a place to work in that expensive city and also organising exhibitions with them. (This expanded network of peers was alluded to in the title of a recent exhibition he put together in Linz, Austria, entitled ‘Artistic Communities in the Age of Social Media.) Even so, Epp is not utopian about the artworld as it stands today—indeed, his actions suggest a desire to outrun some of its limitations—and his art on occasion concerns itself with how monied and speculative the contemporary art scene has become (some of his paintings situate themselves in art auctions, with figures waving paddles). And yet this is the world he moves within; in short, he’s conflicted, humanly so, such that Epp appears not as some oracular figure diagnosing our reality from on high, but down here in the trenches with the rest of us. But, looking at his art, you feel he can see the world as it is, and he pulls off a rare feat; while presenting the messiness of contemporary reality unsparingly, he makes us want to gaze upon it.

Martin Herbert, 2022