FUTURES PAST

27 Oct 2022-28 Jan 2023

PV 27 Oct 2022, 6.30-9pm

Morehshin Allahyari, Juan Covelli, Dominique Cro, Sandrine Deumier, Matteo Zamagni, Lawrence Lek, Kumbirai Makumbe, Entangled Others, Abi Sheng, Shinji Toya, Ryan Vautier & Sarah Blome

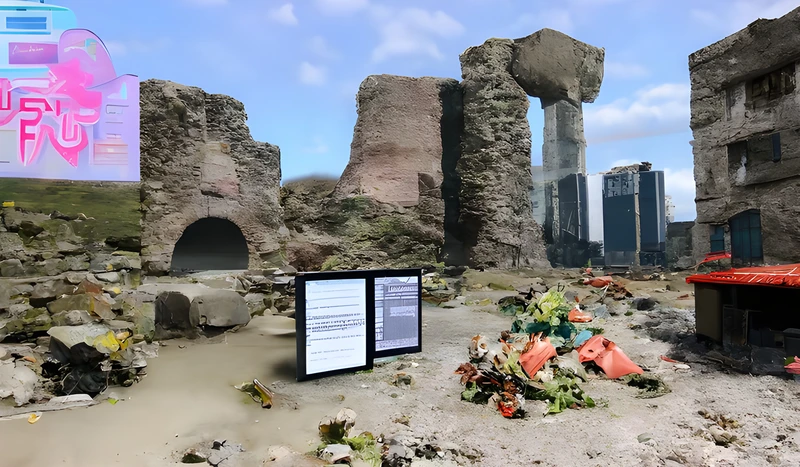

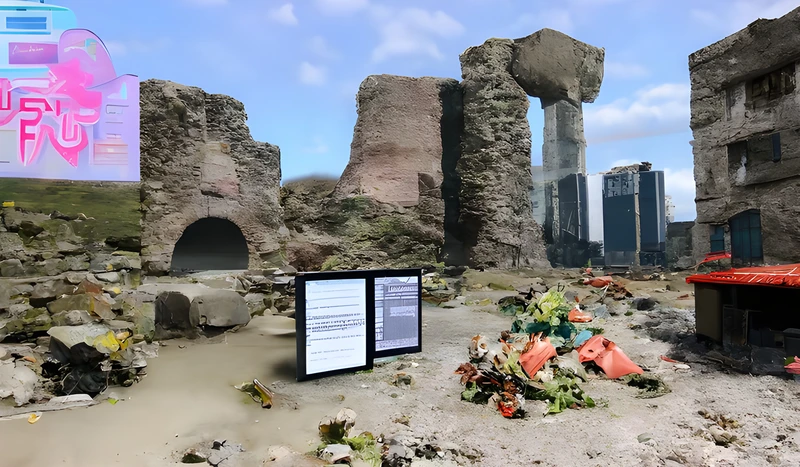

Futures Past takes the viewer on an immersive journey through the excavated ruins of the future filled with digital and sculptural works, interactive and static assets, as well as AI-generated renderings to contextualise the disparate findings. The gallery becomes a site for discovering fragments of media, objects and genre-fluid artwork documenting the perceived notion of futurity through retrospective, historical, orthographical, geological and temporal dimensions.

Mimicking archaeological digs and touristic attractions of historical sites, the exhibition presents digital works that encapsulate ideas around the past, present and future: amalgamated beings, mixed histories, clashes of culture, and worlds within worlds. The works are portrayed as excavated entryways and fragmented and disbanded relics - a puzzle to piece together. We are asked to reimagine the way artefacts are viewed, recounted and told, as well as how they can assist us in denouncing colonial pasts, speculating, narrating, and unpacking the multiple crises in which we find ourselves. The works posit radical views of the future that don’t rely on the retelling of big tech fantasies of power, control and subversion that are built from colonial imaginings, capitalist, patriarchal and imperialist ideologies, but instead emancipate us from the complacency we have been acclimated to. What might become of the future we will never inhabit is not clear - we know where the future is but not entirely what it is. The exhibition covers four modes of seeing - this is not to presume what the future will look like but rather to think about how the future is seen through the lenses of past, present, future and preservation. Adopting the notions Benjamin Noys puts forward, this could be rephrased as “de-inventing” the future and returning to the present as a “fraught and fragmentary site of struggle.”

The gallery takes on a new purpose as a site for archiving and preservation; a mediator for concepts of futurity whose glitched screens and leaky disc spaces are identifiable as belonging to our present, the early twenty-first century, but whose artefacts belong to another time. Now in recovery and recontextualised as excavated portals (a temporal non-place) the works seek renewed attention and frameworks, they become ominous adages as well as bright suspicions of tomorrow. The works have been found to remind us of possible, probable and preferable futures (to adopt the language from Futures Thinking theory) and ask how technology can assist in developing more of an understanding of the hereafter.

Contained within them are ghostly remnants of the nascent and full-fledged critical exchanges surrounding the multiscalar crises of the present, not wanting to be forgotten, forever embedded within our collective memory. In their age of total recall, memory is never lost.

Acting in flux within the exhibition are temporal, cosmological, mystical and fictitious renderings articulated within the terms excavation, future and history. The Western notion of time is linear; time flows as a straight line. On a continuum, the past is to the left, and the future is to the right; events are thus chronologically recorded, one following the other.

To know your future you must know your past is a sentiment shared by many great thinkers and writers of the last century, but Futures Past asks us to reconsider this by looking at our present from the eyes of the future - instead, to walk backwards into the future with eyes fixed on the past. Seeing time and all it encompasses as circular, or nonlinear, allows for more spiritual and progressive articulations on how we might live in the future, present and past synchronically.

In Patricia Waugh and Marc Botha’s book, Future Theory, the interrogation of terms and concepts deemed central to change are categorised into five key concepts – boundaries, organisation, rupture, novelty, and futurity. To use these categories to expand on the works in Futures Past we can build an understanding of how artists are using theories and concepts applied to a constantly shifting world.

Exploring rupture and futurity in the exhibition and addressing climate change, extractivism and the Anthropocene are works by Matteo Zamagni, Entangled Others, Shinji Toya and Dominique Cro. These works provide insights into organic evolutionary processes and electronic evolutionary processes via machine sentience and remixing data.

Thinking through boundaries and organisation, and addressing colonial practices and ownership of relics and artefacts in the exhibition are works by Morehshin Allahyari and Juan Covelli. In these works, one of which has relied on 3D printing as a medium and as a “technology for remodelling thought into new shapes”, a critique on representation as a technology of colonial domination over nature and territory is exemplified. In the (sometimes) open-source method of creation and dissemination of the works, as well as the cultures that the work speaks for, the inclusion of such works aims to expose in-betweens, to engage with empowering the powerless, and questioning the presupposed. Further exploration into the dissemination of data and cultural property is the incorporation of 3D printed objects from the open-source collection Three D Scans, a project initiated in 2012 by Oliver Laric that aims to make museums’ permanent collections available to an audience outside of its geographic proximity.

Conveying novelty and futurity, and addressing post-human and cyborgian threads are works by Kumbirai Makumbe and Abi Sheng as well as the videos by Ryan Vautier and Sarah Blome. These works interrogate the body as a site for emotional emancipation together with the notion of reaching a technological singularity.

Figuring novelty and boundaries, and addressing worldbuilding within the realm of future thinking are works by Lawrence Lek and Sandrine Duemier. The works add gamification to the idea of altered states of presence and memory that exist in digital space questioning our capacity to perceive the living world as a complex entity.

In addition to the floor-based works, fragments of selected artists' works are presented on a display wall akin to museological displays. Unlike traditional display cases, the assets (which include untethered CGI models, 3D printed objects, and gifs) are preserved within the digital and mostly bound to the medium of the screen. By separating out various elements from the artist's work, the wall questions collection, archiving and conservation of digital practices and highlights the importance of treating it in the same way as more traditional and ephemeral practice; holistically and with attention to lineage and provenance.

Media archaeology starts with the archive. Reclaiming an imagining of the future operates within the boundaries of the past; inherently political and forever imbued with colonialist regimes and imperialist orders set out to marginalise and weaponise power, a renewed thinking toward a future we could envisage as livable requires reprogramming of many variables. In the context of an archaeological excavation site, the works become saturated with an inclination for documentation, counting, numbering, situating (temporally) and archiving. The way we understand and treat archival material, and the way material becomes archived changes depending upon the object in question. Unlike digital media archives, analogue media archives should be preserved and not played as “each replay is a partial erasure… Digital preservation relies instead on the frequent rereading, erasure and rewriting of the content”. Unlike earlier models of archiving which seem to freeze time, archiving in the digital sense could be described as an archive in motion. Unearthing these digital findings, reanimating them and replaying them rekindles them and keeps them alive and whole - in direct opposition to that of standardised museum archives and displays which fetishise fragments, fragility and decay. Here, cultural material and ephemera pile up and become fodder for the Earth as decades go by - what do we choose to keep and what becomes discarded to compression within strata?