Carolee Schneemann: 1955–1959

17 Sep-29 Oct 2022

PV 17 Sep 2022, 2-5pm

Hales is proud to announce Carolee Schneemann: 1955–1959, the gallery’s third solo exhibition with the late artist. This exhibition of early work runs alongside Body Politics — the first major survey of Schneemann’s work in the UK, organized by and on view at The Barbican Centre from 8 September 2022 to 8 January 2023.

Schneemann (b. 1939, Fox Chase, PA – d. 2019, New Paltz, NY, USA) was a seminal, trailblazing artist with a far-reaching oeuvre spanning sixty years. Rooted in painting, her experimental practice extended to assemblage, performance and film. Schneemann received a BA from Bard College, NY, and an MFA from the University of Illinois. She held an Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts from the California Institute of the Arts and Maine College of Art. In 2017, Schneemann was awarded the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the 57th Venice Biennale.

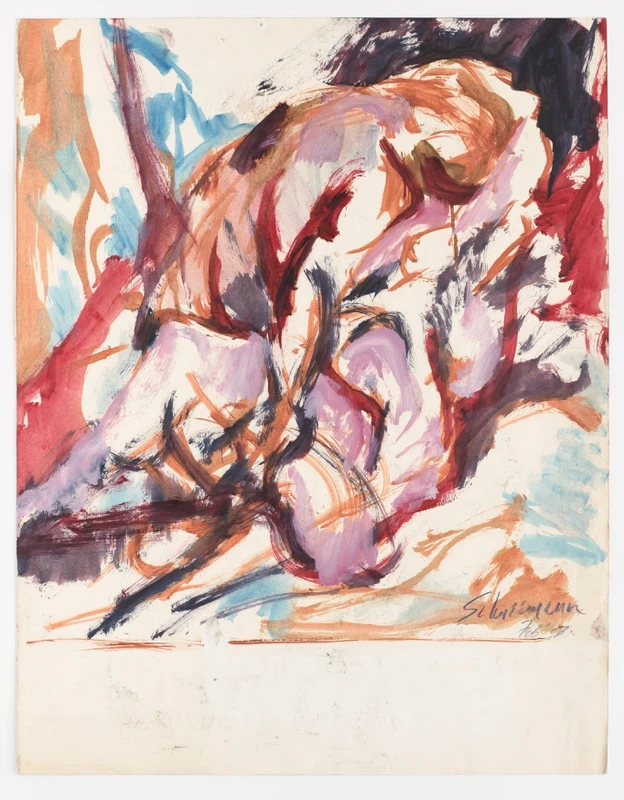

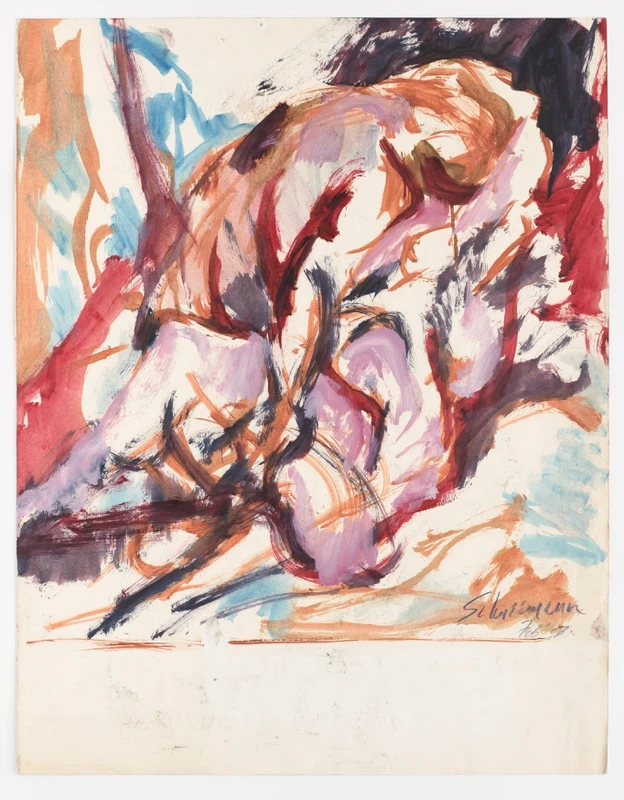

Carolee Schneemann: 1955–1959 brings together significant nude figurative paintings and an early body of drawings, on view together for the first time. Made at a critical period of intellectual and artistic growth, the works demonstrate the importance of the act of drawing—of drawing as action—that would remain constant.

Schneemann drew from an early age; as she put it, ‘I began to draw before I could speak and never stopped drawing.’[1] This exhibition showcases her first mature drawings and paintings from the final years of her education at Bard and Columbia and the beginnings of her identity as an artist. Her time at Bard was tumultuous, in large part due to the great deal of sexism she experienced. Schneemann painted several nude self-portraits in response to the lack of access to professional models and was consequently expelled (temporarily) for ‘moral turpitude.’ In 1954 she transferred to Columbia University’s School of Painting and Sculpture and the New School for Social Research; she graduated from Bard in 1956.

During these years in New York, and then in Bennington, Vermont, Schneemann’s creative milieu was deeply influential to her thinking; her companions and collaborators included composer James Tenney and filmmaker Stan Brakhage. The impact of Abstract Expressionism can be seen in her gestural mark-making — as evidenced by visual parallels between Willem de Kooning’s Woman series of the early 1950s and Schneemann’s Green Figure (1959). A longstanding appreciation for Cezanne’s compositional tools, use of colour and painterly textures is evident in her confident brushstrokes. In N.L. Reading M.P. (1955), Schneemann connects the reclining nude to the landscape, in both palette and the curvature of the body’s undulations. The painting is a study of her close friend, Naomi Levinson reading Proust. The intimate portrait is indicative of their friendship and intellectual discussions around this time, and of the freedom with which she moved between genres and conventions. As Schneemann remembered of reading Proust: “He gave me permission to bring in what I was obsessed with—Jim’s underpants, cats, shards of a pot—which were not permitted in the culture, things that had holding power.”[2]

While connections can be made to her contemporaries, the lines that Schneemann developed over these five years were distinctly her own: In a letter to Levinson in 1957, Schneemann wrote of a visit by Leo Steinberg, art historian and critic who said that her paintings were ‘“vital, valuable…” and perhaps something else with V. And he said to work with landscape and figure as long as I could – that the world rarely offers itself as richness.’[3]

Schneemann’s formalist and aesthetic concerns are rooted in painting and drawing. These works are the crucial precursor to the work’s extension off the page and canvas, to encompass assemblage and performance. ‘Action Drawings’ depict a connection to the physical body and a kinetic movement. Here in the early stages of her life, she is finding ‘action,’ palette, and the body as subjective experience, which would all come to be synonymous with the artist. Indicative of this future, in 1957 she wrote, ‘Every time I work well from the figure I “break” with the figure; for I don’t want “it.” I want its limitless possibilities for forms and spatial expressiveness.’[4]

---

[1] Martin, R., 2017. Painting for pleasure: an interview with Carolee Schneemann. [online] Available at:https://www.apollo-magazine.com/painting-for-pleasure-an-interview-with-carolee-schneemann/ [Accessed 14 July 2022]

[2] Stiles, K. (ed) (2010) Correspondence Course: An Epistolary History of Carolee Schneemann and Her Circle, Durham and London, Duke University Press, p. 17. Quote from footnote 49, pp. 18–19

[3] Ibid, p. 17

[4] Ibid, CS to Stan Brakhage, 4 April 1957, p. 9