David Altmejd

23 Nov 2022-21 Jan 2023

Canadian artist David Altmejd opens his first solo exhibition with White Cube in London featuring new sculpture.

On the ground floor of the gallery we encounter a human figure with the ears of a hare, seated in yogic pose. Its giant ears, stretching almost to the ceiling, seem to probe the limits of the room, while in front of it is a burrow from which the figure appears to have excavated the very matter from which it is made. The contrast of these feet of clay and ears spread like dragonfly wings suggest that a transformation is occurring, from the material to the ethereal.

The Hare is the presiding spirit of the exhibition, whom Altmejd recognises as the Jungian archetype of the Trickster. According to Carl Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious, our ancestral memories are represented by certain universal themes and roles which appear throughout our literature, art and dreams, and these archetypes can explain our psychology. Trickster is irrational and capricious, a prankster and shapeshifter. He is Hermes, audacious thief and messenger for the Gods, and Loki the gender-switching master of disguise. For the Yoruba he travels between heaven and earth as the contradictory character Eshu, and to First Nations people he is Rabbit, Raven or Coyote, the rule breaker whose mischief brings about change. He surfaces in African-American folk tradition as Br’er Rabbit, and even appears in animated form as Bugs Bunny. The essayist Lewis Hyde, author of Trickster Makes This World (1998) tracks Trickster into the modern age, subsumed into the role of the artist, and makes a case that this playful, subversive and disruptive force is indispensable to the vitality of our culture.

Altmejd has always sought to absolve his conscious mind from the responsibility of creation, instead attributing his sculptures with their own agency. The crystals he often uses are, in the sculptor’s lexicon, an energy source with which the works are charged, and he has made works featuring multiple hands that appear to clutch and mould at their own substance, just as the seated figure seems to have done. So the Trickster, the mercurial catalyst for transformation, messenger from the subconscious, presented himself as a welcome proxy for the artist, freeing his imagination and spurring it to wilder transformations.

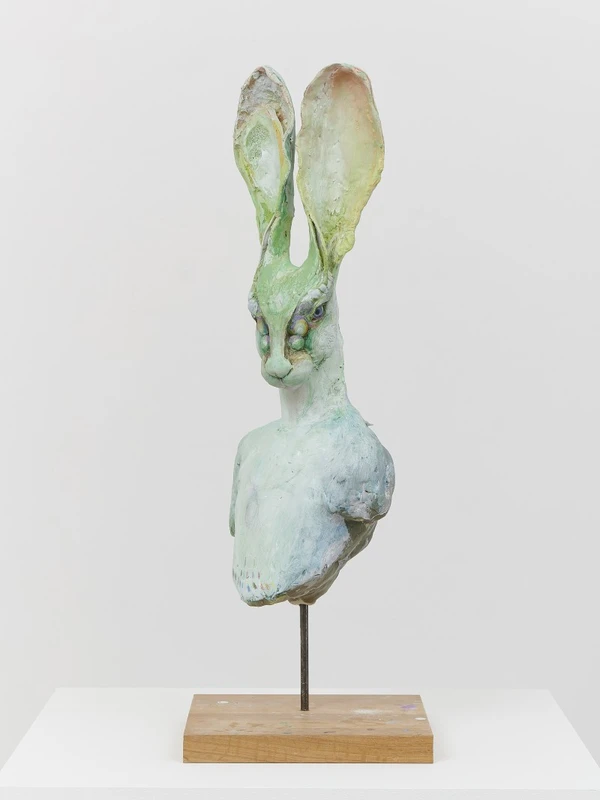

Rowed plinths line the lower gallery, mimicking a classical sculpture court and displaying a fantastical array of bust and heads. Sometimes fragmentary and possibly time-worn, they suggest archaeological finds, parts of animal-headed deities, but might also be extra-terrestrial specimens or the result of genetic experiments. Trickster’s shapeshifting powers are truly unleashed, and we meet the Hare in many forms, from cartoon-like to disconcertingly human. His signature ears, majestically erect, comically jaunty or limp with despair, are semaphore flags signalling emotion: they are reduced to vestigial stumps, exaggerated into sails, and in one case formed from the split carcase of a sperm whale. Caught mid-metamorphosis, an elegant hare grows lizard scales, ears transform to leathery batwings and a belly swells with the sleek black and white curves of a killer whale. The most human of the company are given archetypal designations: The Magician, The Other, Young Man, The Mother. Acting as his own analyst, the artist identifies this crowd of characters as manifestations of different aspects of his personality, allowing us to perceive the exhibition as multi-faceted psychic self-portrait.