Conversations with Memory

22 Jul-22 Sep 2022

PV 21 Jul 2022, 6-8pm

A group exhibition featuring new works by Diane Chappalley, Bartlomiej Hajduk, Francisca Sosa López and Merve İşeri

Our memory is a more perfect world than the universe:

it gives back life to those who no longer exist — Guy de Maupassant

Exhibition runs 22 July - 4 August 2022, and continues 8 - 22 September 2022

Essay by Matthew Holman:

How can we be sure what we remember? How can it be that so often the past feels more real than the hazy right now, as though it’s a bunch of wildflowers that you can hold in your hands, blazing a tirade of iridescence in summer’s hues? When we lose someone important to us–the betrayed friend who can’t forgive, the parent all wired up in the hospital bed, that green-eyed stranger ten years ago–then they can often feel closer in the carousel of images that make up our imagination than if they were standing right in front of us. How can that be so? We often want our art and literature to demonstrate a desire to transcend time, to transcend this sense of having lost in our own lives, or what the philosopher Martin Hagglünd has called ‘an epiphany of memory, an immanent moment of being, or a transcendent afterlife.’ But isn’t it true that the pain of having lost something or someone is conditioned by the fact of having cared for it in the first place? Isn’t that the starting point for so much great work?

These are questions asked by the four artists in the present exhibition. All are in their late twenties or very early thirties, all are concerned with the dilemma of remembering against the tide of forgetting, and all are expatriates, exiles, or émigrés of some kind, who have tentatively made London home. Bartłomiej Hajduk was born in Poland in 1990, the year of the May elections when the country transitioned from communism to parliamentary democracy. Born in Switzerland, Diane Chappalley’s painting practice is fiercely focused on the tactility and abstract quality of the natural world. Francisca Sosa López has said that her work ‘is based on the complicated relationship’ she has with her home country of Venezuela, and the ways that ‘memories and music [form]… sensations and interpretations of “…home.”’ Merve İşeri was born in Istanbul and came to London in 2015. She arrived on a tourist visa, and used the reams of government paperwork for the resettlement process as a canvas to overlay bold brushstrokes in vibrant colour. Remembering the thresholds of what was lost, the cities and the continents as well as the people along the way, animates these works: they all operate on the border between a place of origin and where we might travel to.

In a new diptych, The Silence That We Hear (2022), Chappalley has painted a chorus of bursting flowers–rudbeckia hirta, echinacea, cornflower, calendula–set against a hauntingly maroon landscape that blazes without pause. These flowers burst upwards, and the soft glint of a shimmering cobweb outstretches across the glad petals. The artist has primed the canvas of the diptych with a transparent coating that has created a firm and applied thickness to the texture of the work. Speaking to the energetic forms of life that is the painting’s subject, the applied coating creates an earthiness as the densely applied oil paints sit and consume the surface. In the hinterland below, a female body in luminous off-white–asleep? daydreaming? buried?–has her eyes closed. Where on Earth are we? Is this a scene of death, a rumination on the ways that the cyclical forces of nature reconvene as we perish? Or a painting that asks us to think about the passing of seasons, even or especially as extreme climate conditions disrupt its rhythm? In either case, life and death are held at once.

Chappalley has recently produced a series of ceramics that sculpturally correlate to the spindly, untutored wildflowers in her paintings. These works, which look as though they are half-hovering on their plinths, delicately poised as though they could be held in one’s hand and extinguished in a half-beat. ‘My favourite quality about [Henri Fantin-Latour] is that he gives life and then threatens that life in the same picture’, writes the artist Jennifer Packer: ‘Some of his flower still lifes feel like they’re choking on this grey air.’ I see Chappalley’s paintings and ceramics in a similar way. You could take these flowers in your hand. They are dying in the midst of life.

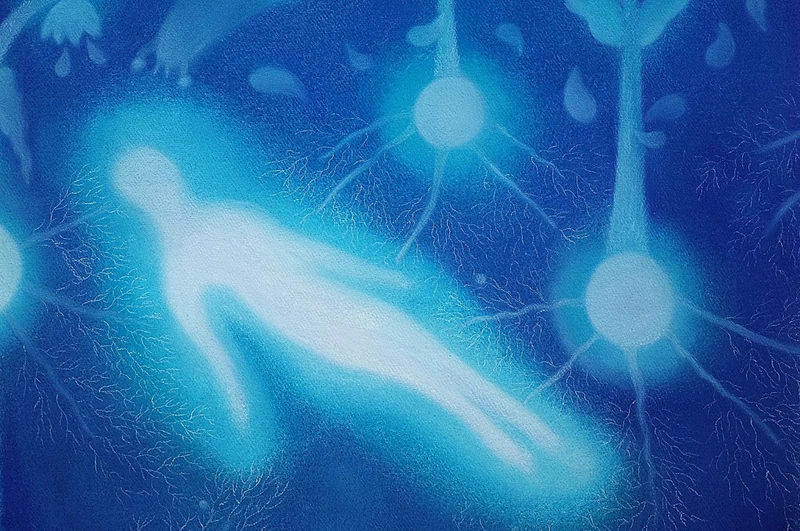

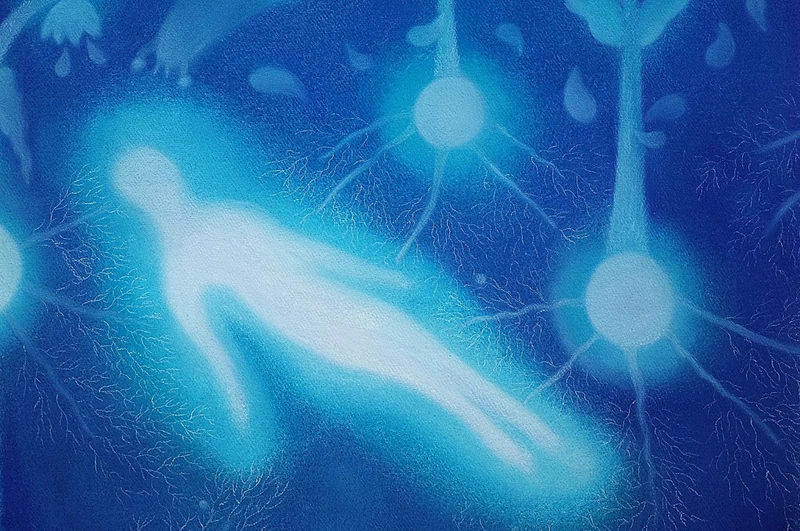

With its incandescent humanoid form and shape-shifting floral accompaniment, Hajduk’s Ogród pośmiertny (The Garden of Afterlife) (2022) feels like a companion piece to Chappalley’s The Silence That We Hear (2022). It’s extraordinary how very deep the soft pastel blues are here, as though we are submerged at the bottom of the ocean or hovering in the upper recesses of the sky, proximate to the radiant sun. It’s a compelling thought to learn that the Polish word for ‘blue’, ‘Niebieski’, is the same for ‘heaven’, or literally ‘from the sky, from the heaven.’ Blue is the endgame. Like Chappalley, Hajduk has created a transitional landscape, a place of passing through, and the body is set adrift. Produced on thick rag paper, the composition narrates the movements of a bizarre ecosystem of giant snails and Delphic amphibians in a way that suggests that everything in this otherworldly province comes into view only to be already marked by a moment of its transition away from our field of vision. It’s a work that seems to capture something of the irredeemable past and sonorous present in the same tract of space. As I was writing this piece, I came across a new poem by Peter Gizzi, in which he begins: ‘Hold on to the afterlife of the beloved, it’s the only thing that’s yours.’ Both of these works by Chappalley and Hajduk represent the atmosphere if not the actuality of an afterlife, and of a spectral sense of an absent or lost beloved who is imagined in a meadow, or the sea or the sky, almost within reach.

Before she left Venezuela at the age of eleven, returning only periodically to visit her parents in the suburbs of Caracas, Sosa López studied at an All Girl’s Catholic school where nuns taught her the gospels and embroidery. Frustrated that her brother was not educated in the same way, and that the skills she would gain were predetermined by her sex, Sosa López has since redoubled new purpose to these old objections and returned to her childhood experiences of stitchwork, of tying together composite parts and creating new wholes from the fragments. Huge sweeps of embroidery fasten these canvases, evidence of reaching and stretching like the labour of a sloth high up in the trees. In the series of works shown in Conversations with Memory, the artist has focused on the figure of the sloth Ramona, who climbs the vegetation and yagrumo trees of her parent’s Caracas home, and so named after a character in the lyrics of a popular song that also goes: ‘Nuestro insólito universe. 5 min recorriendo nuestro mundo sorprendente. [Our unusual universe. Five minutes touring our surprising world]’. In some ways, these paintings animate these lines: what a strange and surprising world we live in, they seem to say, and in this journey of pleasure as we travel from home to an elsewhere and back again, don’t move too fast. Ramona certainly doesn’t.

In an epistolary address to the fugitive sloth, Sosa López cannot reconcile her feelings of cultural dislocation by having relocated to London and not stayed in Caracas, despite acknowledging the reasons for the move, and is held in a comparative bind: ‘I can’t replace the tropical rain with the light drizzle. I can’t replace the macaws with the pigeons. I can’t replace the foxes with the sloths. All of it is engrained, intertwined, interwoven and sewn into my soul.’ The sloth becomes a stand-in for the wild, brilliant palette of home. But the paintings seem to be complicit in calling out the fictions of home, too, and the ways in which the topographies of youth and early adolescence–the places where our past selves once inhabited, and no more–are reframed and re-remembered in our imagination.

İşeri’s paintings start out as imagined constellations, spread out like Orion’s Belt or Ursa Major, with small white circles–like the ones that are affixed to sold paintings at art fairs–that provide the basis for structuring the composition in its most rudimentary form. The artist does not make preparatory sketches, and so these enigmatic paintings ask us to think about relationality in its broadest sense: what is our position in space, within the world of four dimensions? But, more than that, what is our own relationship to the world of the imagination and our relatedness to those who are no longer here? These pictures defy easy categorisation: they are joyous, gestural, and responsive to the movements and the curvatures of nature. But it’s possible to see even in these aquatic and amorphous forms, which meander and pulsate in the way that only imagined forms can, the politics of İşeri’s earlier experiments on the bureaucratic visa papers. İşeri’s pictures document a profound sense of transience and the stasis of living life on the fly and in-between, of marking out our lives in an operative present, without knowing where we will call home. If these paintings are in conversation with memories, they are also ‘in memory of’ a time and a place long since lost, as all of these paintings seem to be–whether that is a childhood home, a continent, or a wildflower in the long meadow.