Hadi Fallahpisheh: Young and Clueless

9 Oct-20 Nov 2021

Dear Hadi,

I heard about you long before I met you. The painter Amy Sillman would sometimes corner me at openings and tell me that I had to meet a student of hers. In that Hans Ulrichian “it’s urgent” kind of way. She was so effusive that I was more than a little suspicious. I never did follow up.

Years later, I came across your art at a show at Tramps, the gallery in the mall on East Broadway. I was really into one piece in particular, which featured a large rat behind bars. The rat was as tall as me and had a little mouse hole where his dick was supposed to be. It made me laugh, even if it was a little macabre. Was the rat smiling or grimacing? A victim or a villain? Why was he wearing sunglasses indoors? It was all a bit unclear. But pleasurably so. I appreciate ambiguity as much as the next person.

At the time, Trump’s immigration policies had achieved peak shittiness, and the prison bars, as well as the Chinatown gallery’s ridged walls—the legacy of having once been a retail space—added to the general carceral vibe. I later discovered that in a fit of desperate anger over the Muslim ban, you had made but not deployed a series of Molotov cocktails to lob at Trump Tower. Chapeau. I may or may not have texted Sylvia about “this new Iranian painter…”

Well Hadi, you’re not a painter at all. How embarrassing. This realization arrived only when I went back to the show and we talked. You told me about your parents, both of whom are photographers. “I grew up in the darkroom,” you said. You described your process, which involves hurling objects, mostly balls, at photo-sensitive paper, then making marks and burning holes into the same paper with a flashlight.

The end result is arrestingly vivid surfaces in Kool Aid hues of pink and red and yellow and blue, which get stretched onto a canvas, much like a painting would. I’m interested in the role chance plays in your work, how you can’t anticipate the color that will emerge from the darkroom until the very end. A photographer without a camera, you’re improvising, playing in the dark, spinning the wheel of fortune. An existential magician.

Beyond the rat, I’ve since learned that your art is populated by other members of the animal kingdom: your post-Disney dogs, cats, and mice are human-animal hybrids, suggestive of a rich allegorical universe. I mean, what’s not to love about a dog daydreaming about a cat fucking a mouse beneath disco balls? These non-human humanoids heighten the atmosphere of naughtiness, of transgression, of breaking rules. Of art I mean. I’m reminded of Deleuze and Guattari’s discussion of Kafka. How “becoming animal” signifies an affront to the established order of things, a movement from major to minor. So… what draws you to animals in the first place?

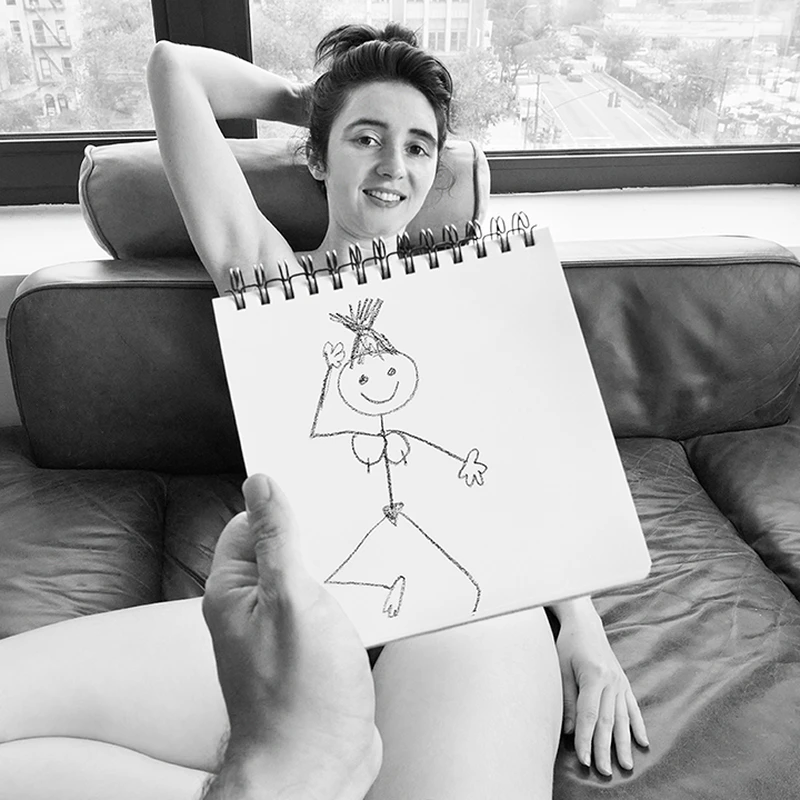

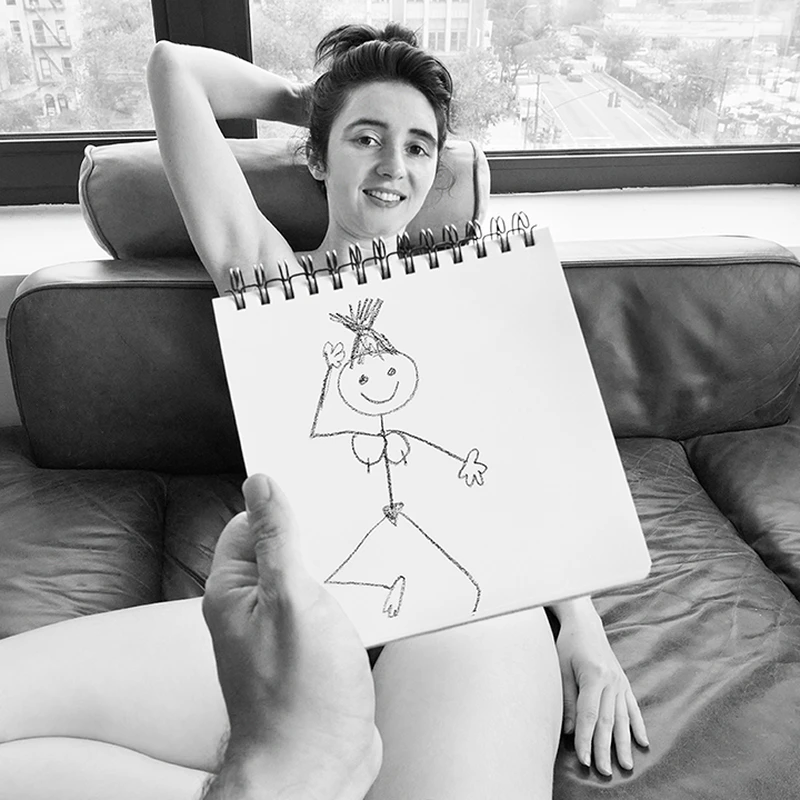

Hadi, I imagine some people consider your work irreverent, rude, even childish. Is that fair to say? I do find that questions related to power, desire, and mobility are front and center. Even if your art might feel like the intellectual equivalent of a whoopee cushion. You’ve named your new shows in Athens and London Young and Clueless. Is that because you’d like to pre-empt this line of critique?

Vis a vis childhood, I’ve been thinking about mine. Spurred on by a therapist, I recently recalled how I used to fashion my own private family with stuffed animals, which I would arrange in a cardboard box in the closet. My doll children were so pliant. I gave them embarrassing names drawn from my favorite TV shows and they did everything I wanted them to. They never talked back.

In Athens, you’ve arranged a series of stuffed animals in a sort of ceremonial arch, their heads submerged in ceramic pots, a little bit like “hooded man” at Abu Ghraib. In place of eyes, nose and mouth, you’ve scratched the surface of the pots, creating the impression of defaced emoji faces. The animals can neither speak nor move their heads. Oh Hadi, childhood can be so dark. What was yours like? Did you spend a lot of time in your bedroom listening to Madonna like I did?

There are many bedrooms in your work. Bedrooms and prison cells, bedrooms as prison cells; the domestic as uncanny nightmare. The use of pretty floral textiles in your sculptures only adds to the Little House on the Prairie Laura Ashley nightmare vibe. Is that intentional? What about the bed in your Athens show, which feels so punitive, with its echo of prison bars along the headboard and base? It’s so austere!

In London you’ve erected a sort of village. A pretty square with a palm tree, complete with a picket fence arranged in what feels like the rudimentary stage setting for a school play. It’s a departure from your earlier work, less interior-oriented, filled with scenes of animals frolicking, shooting the shit, taking part in sexual hijinks al fresco. When I asked you why you’d been thinking about villages you replied, “But we’re all from villages.” The way you said it gave me a little chill. “There’s no hiding in a village,” you added, and I agreed.

We miss you in New York, where apropos nothing and everything I’ve just written, undergoing psychoanalysis is “like drinking water.” I’m translating from the Persian, but I know you know what I mean.

Love,

Negar

Text by Negar Azimi