Tip of the Iceberg

12 Sep 2021-16 Jan 2022

Shaun C. Badham, Becky Beasley, Kathrin Böhm, Graham Burnett, Gabriella Hirst with Warren Harper, Anna Lukala, Mary Mattingly, Uriel Orlow, Rachel Pimm, Alida Rodrigues, Zheng Bo

This exhibition explores the relationship between art and alternative growing practices, which are increasingly coming together in pursuit of climate action and social justice. New and recent works by local and international artists explore three key themes: the notion of the ‘commons’, i.e. our common right to the earth’s natural resources (air, water, soil, land); how plants can be considered as both witnesses and agents across history, and how local hidden economies can act as catalysts for wider change.

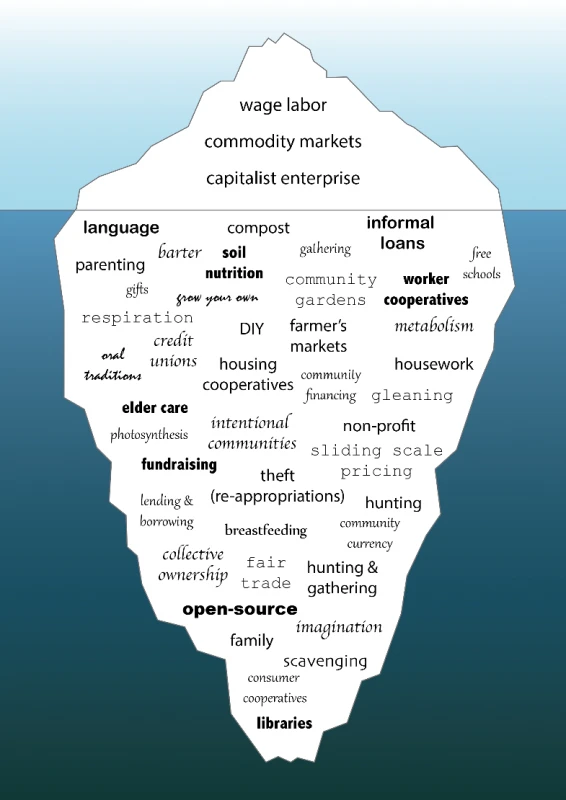

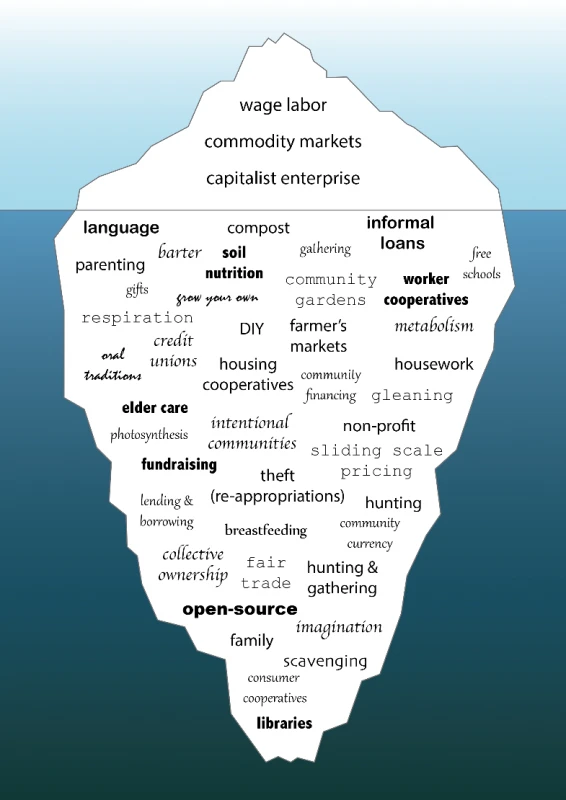

The title refers to the image of an iceberg as a visual metaphor, first used by feminist economist geographer J.K Gibson-Graham to explain the diversity of economic systems and to symbolise the limiting effects of representing economies as dominantly capitalist. They argue that monetary transactions, wage labour and corporate or commercial institutions are like the peak of an iceberg, hovering over a mass of unaccounted labour, gift economies, non-monetary exchanges and human self-organisation. In this context, the use of the diagram highlights how many environmental practices that are so important to sustainability sit below the ‘Tip of the Iceberg’. The title also offers a nod to the precarity of which regions might survive in the event of sea-levels rising. Southend is in the first 10% of UK towns to be flooded by rising sea levels, making climate action an imperative rather than an option.

Whilst the scale of the ecological crisis can seem overwhelming when viewed globally, ‘Tip of the Iceberg’ explores how individual and collective action can have local impact to tackle some of the environmental problems we face, whilst also connecting to other national and international initiatives and debates.

The artworks in Gallery One focus on eco-systems and environmental work that exist within Southend-on-Sea, the Estuary and South Essex through art and community projects, whilst also acknowledging their historical foundations.

Presented as a poster and as a wall piece within the exhibition, Southend-based artist and permaculture practitioner, Graham Burnett has created a new drawing, Roots and Branches, a Psychogeographical Mind Map using the metaphor of a tree to represent the ecosystem of connections between people, projects, spaces and actions that operate ‘below the surface’ of Southend-on-Sea, working towards a resilient local future in times of climate change, energy descent, financial instability and post-pandemic uncertainty. The central tree structure of the mind map was drawn using charcoal made from willow harvested from Burnett’s allotment, then pyrolised in a mini-kiln in his home wood burner, representing direct connections with the landscape and place of Southend. The drawing is also a ‘tip of the iceberg’, as it can only represent a sample of what is going on in Southend.

Kathrin Böhm will create a new wall tape drawing for the exhibition that uses the iceberg above and below the waterline as a visual metaphor to explain the diversity and interdependence of economic systems and practices that exist within the economy at large; within environmental practices; and within the ‘multi-verse’ of artworlds. Throughout her practice and as part of a growing academic discipline exploring ‘diverse economies’, Böhm seeks to challenge existing conventions of what and who is valued, made visible and acknowledged for their labour and contribution to society by exploring alternative modes of economic and collectivised sustainability.

A new work by Shaun C. Badham, PLOT: The Peoples’ Landscape explores the social, cultural and historical connections between current day society run allotments in the Borough of Southend and historical alternative uses of land such as the Plotlanders (Plotlands refers to small pieces of land laid out in regular plots on which a number of self-built settlements were established in the south-east of England from the late 1800s and up to the Second World War). The Plotlanders could be described as both a community, a movement and a way of life which although no longer exists in the same way, could be seen to live on through today’s allotment societies; particularly through a DIY sensibility, growing your own and community care via working the land.

This new body of work will include a series of map drawings of five society run allotments developed through an ongoing collaborative process with the community who work the land. Through these conversations a series of oral histories will be captured and made available as a digital podcast, exploring the thematical links between the communities and time periods. Once complete each drawing will be re-printed and gifted back to the allotment societies as a record.

In October 1947, landscape architect Lancelot Arthur Huddart was commissioned to re-imagine the Kursaal’s grounds. Located upon Southend’s seafront, the Kursaal opened in 1901 and was one of the world’s first amusement parks. During the Second World War, however, most of Southend was commandeered, due to its location along the Thames Estuary being perfect for naval fleets. Regular bombings upon this once thriving seaside town saw much of its buildings and public greenery devastated. Huddart worked for London County Council’s Parks Department at the time, before his retirement in the late 1960’s. This drawing, along with some of his earlier landscape drawings, are now housed within the Museum of Natural Rural Life at the University of Reading. He had planned to install a flowing rock waterfall, that would illuminate come nightfall, with winding pathways through beds of wild plants, irises, and a variety of roses. Huddart’s drawing, titled Suggested Garden Improvements ‘The Kursaal’ Southend-on-Sea,1947, was a proposition to regenerate Southend and increase its green spaces, returning the town to its former glory as a popular tourist destination. We can find similar motivations within the Council’s current plans to mitigate the effects of climate change. Increased flood risks, unprecedented summer temperatures, and rising levels of greenhouse gases, can all be significantly reduced through the introduction of urban greening. Huddart’s drawing emerges from a different moment in time, yet the objective behind it resonates all-the-more urgently today.

Documentation of public artworks by New York based artist, Mary Mattingly, will be presented alongside a new map of the Thames Estuary that highlights an array of environmental projects. Here, ideas for soft infrastructure barriers, land reclamation, responsive architecture, tidal and marshland ecotones, and regenerative food systems including saline farming and floating farms have been diagrammed onto a map of the estuary. The map is a provocation to instigate further brainstorming about different means of mitigating damage from sea level rise while strengthening regenerative food and water systems.

The video documentation shows Vanishing Point, an ambitious two-part installation co-commissioned by Focal Point Gallery and Metal for Estuary 21, comprising of a learning centre located on Southend Pier, and a floating sculpture moored in nearby waters. This project considered how the plant life of the Thames Estuary has evolved and responded to a changing climate over millions of years, and how this knowledge might be used as a prediction for a nearing future. This is presented alongside documentation of her socially engaged work in the US that explores how access to the ‘commons’, i.e. the cultural and natural resources that should be accessible to all people, has in reality often been determined by corporate and commercial interests. Swale, is an edible landscape on a barge in New York City to circumvent public land laws that make it illegal to pick food on public land. Swale led to the creation of the “foodway”, a permanent edible landscape in Concrete Plant Park, the Bronx in 2017. This “foodway” is the first time New York City Parks is allowing people to publicly forage in over 100 years.

Anna Lukala shares her studies into plants, the cultural history of South Essex and natural pigment research, through an installation revealing her exploratory practice that is driven by curiosity and intuitive experimentation. Offering a ‘behind the scenes’ opportunity for visitors to look and learn about traditional methods of making pigments and inks, Finnish-born Lukala aims to bring back vibrant colours and dyes that illustrate the material culture of her adopted local area around Southend, bringing undocumented techniques and processes from the past into the present through presenting them in a public gallery setting.

Lukala describes, ‘The central themes of my practice are sustainable explorations of local botanical and mineral colours. I am specifically invested in the process of the slow and mindful practice of growing, foraging, harvesting, tendering, with a big emphasis on gratitude and land stewardship. I am fascinated with historic ways of processing and extracting colours, from plant and mineral sources, whether for fabric dye, ink, paint, watercolour or dry pigment medium. I work with a sustainable ‘from soil to soil’ ethos in reciprocity with nature, and a consideration of finding methods of reduced energy and water consumption in my processes. Inspired by the origins of natural colour, its use in history as a creative medium within the arts and craft movement, I am also inspired by ancestral folk traditions that predated synthetic pigments. My specific concerns are the disappearing of these material cultural practices and the lack of records of these traditions in local historic context.’

In Gallery Two and Three, artworks by international artists share their research and visualisations of specific plants and horticulture in order to investigate shared and often contested histories.

London-based artist Alida Rodriques produces compositions that use botanical imagery combined with found 19th century black and white portrait photographs to explore the issues related to archive, memory and the formation – or denial – of history. For this exhibition, the artist highlights the strange and unique plant, Welwitschia, found only in Angola, Rodrigues’s homeland. An adult Welwitschia consists of two permanent leaves which grow continually for up to 1500 years without shedding, and as such is unique in the plant kingdom. Welwitschia is thought to be a relic from the Jurassic period, surviving in an environment that slowly but progressively became more arid, whilst all its close relatives long since disappeared. When ‘discovered’ by Austrian botanist and medical doctor, Friedrich Welwitsch, in 1859, Director of Kew, Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker in 1862 named it after the explorer, despite the fact that Welwitsch himself recommended that it retain its native Angolan name, n’tumbo.

Rodriques uses imagery of the strange, alien like leaves and sexual organs of the plant to create wallpaper that offers a backdrop for two new works, in which embroidered plants mask the faces of individual 19th century sitters in found portraits. This work highlights how today’s circulation of images, or what is missing – such as formal photographic portraits of 19th century black people from the African continent – create an absence of visible history, resulting in a form of erasure of memory. This ‘history of forgetting’ is echoed in the rewriting of indigenous botanical knowledge by 19th century explorers from Europe.

Sub Rosa is a new presentation by Australian artist Gabriella Hirst with curator Warren Harper, Director of The Old Waterworks, Southend. It explores the connections between community gardening, the red rose of England, and historical and enduring violence of nuclear ammunition as part of an ongoing botanical research project, centred on a rare species of garden rose developed in the 1950s, called the Rosa floribunda or Atom Bomb. Since 2018, Hirst has brought the Atom Bomb rose back from the point of extinction, propagating it in collaboration with community growers through collective grafting and cutting sessions, and using it as a vessel to unpack broader ideas around British Nuclear programmes, and the violent legacy of the British colonial historic approach to ‘gardening the world’.

Overall, the project ‘How to Make a Bomb’ aims at distributing these roses into the British soil and within communities as a mutual care initiative, in parallel with a period which has seen a rise of war rhetoric and nuclear rearmament within global politics and media. Another manifestation of this project, ‘An English Garden’ was recently commissioned as part of Estuary 2021, sited in Gunners Park in close proximity to Foulness Island, where Britain’s first atomic weaponry was assembled and disembarked for testing on unceded Indigenous Lands in Australia. Raising unknown and difficult histories to Southend, the work was removed from the site prior to its agreed end date following intense political pressure from a small section of the community uncomfortable with the narrative.

Sub Rosa, meaning ‘under the rose’ (a Latin phrase denoting confidentiality and secrecy, used to define political meetings where what is discussed remains off-the-record) will reveal the thinking and research in the form of original drawings overlayed with nuclear fallout maps, as well as present ‘Atom Bomb’ rose plants at different stages of growth, propagated by the Southend community through a ‘How to Make A Bomb’ instructional rose grafting workshop on 12 September.

Becky Beasley will present a new set of eleven poster format prints each combining a single page scanned from Paul Nash’s extraordinary late essay, ‘Aerial Flowers’ with a section of text extracted from Beasley’s 2018 publication ‘Two Plants in Dip’, a parallel portrait of the artist’s mother and the octogenarian, reclusive, Alien Plant expert, Eric Clement. The book reflects on the future, via botanical conversations between these two friends and with the artist. The selected extracts each offer a proposal for unregulated horticultural action – for example how ants move seeds for Hellebores or ‘exploding’ seeds. Like other series by Beasley, each print also include the date and gallery details as part of the design, locating them in space and time.

Alongside these prints, Beasley will present a new sculpture, comprising of a grey Ann Demeulemeester coat which has been moth eaten. Hanging on a vintage 1940’s wooden standing screen, covered with seeds, the coat will gently sway as if at sea. Sticking out of the pocket will be a well-thumbed copy of ‘Two Plants in Dip’. The seeds reference part of the text where Eric and Beasley talk about how alien seeds are less likely to enter the UK now that produce is ‘purified’ before entering the country. This work explores alien plant immigration as a way to highlight the importance of diversity within society and also suggests an action proposal for activism in the form of attaching seeds to clothes when returning from other countries.

Uriel Orlow presents Geraniums are never red, an ongoing work which explores how the red geranium, planted throughout British parks and gardens aren’t, botanically speaking, geraniums at all, nor are they British. In fact they are pelargoniums and were first brought to Europe – and misidentified – after 1652, when the VOC (the Dutch East India Company) established a permanent settlement and a Company Garden at the Cape in South Africa and started to bring back new botanical treasures which became mainstays of European gardens. By the time the confusion between the two species was identified and resolved, ‘African geraniums’ had been around in the UK for 150 years and British commercial growers and gardeners were reluctant to give up the familiar name. In Focal Point Gallery 3, a large billboard image of classic coastal scenes in California and Zurich, each with a geranium bed in the foreground, is accompanied by a rack of postcards depicting scenes with geranium beds at each location the work has been exhibited prior. For this presentation, two new postcards of Southend-on-Sea’s sea-front – with red geraniums – has been added to the collection. Geraniums are never red explores ideas of botanical nationalism, in particular the way plants, including those ‘naturalised’ become adopted as quintessentially traditional.

Rachel Pimm exhibits a new work, weeds by the moon, 2020-2021, which presents an ongoing collection of images of edible and medicinal plants in the form of a thirteen-point lunar almanac, a diagram, or moon-dial. This is presented as a clock which is disobedient to the Gregorian calendar measurements of days, hours or minutes (introduced in October 1582 by the Catholic Pope Gregory XIII, the Gregorian calendar is now used across most of the world). The plants selected are all freely available growing wild across the UK, and therefore require no private land ownership, nor cultivation and so attention is redirected from commercial productivity into the gentle flux and natural cycle of changing growing seasons.

Presented outdoors on Big Screen Southend and on Focal Point Gallery’s website, weeds by the moon functions as a clock tower without numbers, in which time is measured to a different beat from ‘Greenwich Mean Time’. The viewer can pause, rewind, fast forward or skip around to use as a resource to identify, taste and prepare wild foods and medicines for free, as a means to connect past, present and future traditions and practices. This pausing of time reveals the contents of a rich selection of sources in the form of a bibliography, alluding to universal practices of collective collating and passing on of herbal knowledge from many individuals about how to ‘read’ weeds as an open resource for common use.

‘Survival Manual 2 (Hand-Copied 1945 “Taiwan’s Wild Edible Plants”)’, 2016 by Zheng Bo is a hand-copied facsimile of a book that was published in March 1945 by the Japanese in Taiwan, five months before Japan’s surrender in WWII. The preface of this guide to local, edible plants states: “At this critical moment of the sacred war, the survival of the empire depends on winning the war on food.” Presented in a display case in the gallery’s entrance, this Survival Manual, one of an ongoing series, emphasises a core theme of Zheng’s wider social and ecological practice: the politicization of food.