Jane Dickson

b. 1952, United States

American painter, born 1952

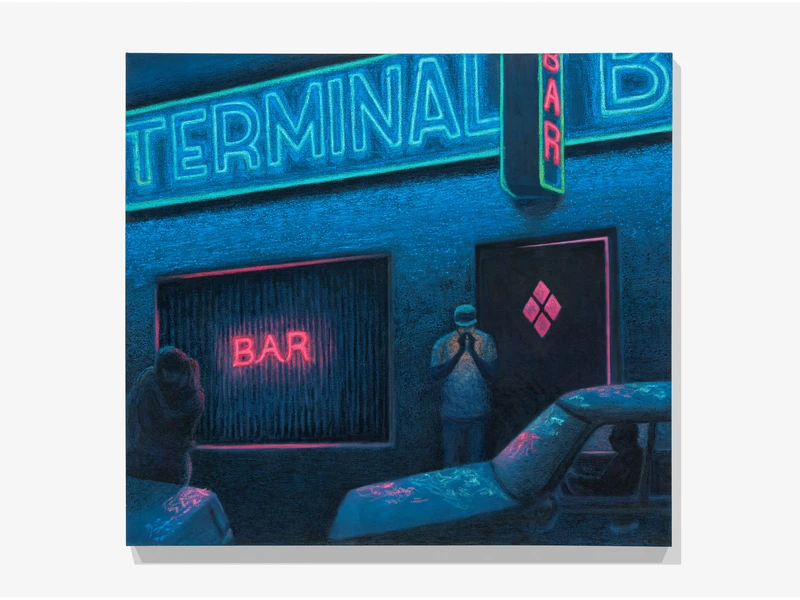

In a photograph taken by Nan Goldin in 1984, Jane Dickson stands outside 43rd Street Seafood. The portrait is taken at night, but the image is radiant: above Dickson, in red, the part-illuminated signage of the restaurant that frames her; to her right, assorted neon beer signs and a fluorescent lettering reflected in glass. In palette, location and formal construction, Goldin’s portrait provides a fitting introduction to the nocturnal metropolitan scenes that Dickson has produced since the 1980s. Predominantly realised in oilstick and acrylic on unconventional synthetic materials, Dickson’s renderings of strip clubs, casinos, carnivals, demolition derbies and, most notably, Times Square, revel in the garish artificiality of our hyper-constructed world while refusing to lose sight of those who linger within. ‘Dickson is the most clear-eyed, factual of painters’, writes novelist Chris Kraus, ‘but what is subtly radical about her work is her ability to render the ugly uniformity of exurban construction in a manner which is not at all dystopian.’

Dickson was born in Chicago, Illinois, in 1952. In 1970, following a year at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, she spent two years studying social anthropology before receiving a BA from Harvard University and a Studio Diploma from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. That Dickson showed an early interest in human behaviour feels appropriate for an artist who would not only devote herself to the tireless chronicling of the lived urban environment, but one who, upon moving to New York in 1978, would become affiliated with the artist collective Colab. Involving such artists as James Nares, Kiki Smith, Walter Robinson and Dickson’s future husband, Charlie Ahearn, Colab brought its collaborative and multidisciplinary work to the masses via non-conventional means, bypassing established venues in favour of pop-up exhibitions and cable TV shows. As Robinson recalls in A Book About Colab (and Related Activities) (2015): ‘We were a gang of young artists who had nothing to lose’.

In 1980, Dickson moved to Times Square, where she worked as a designer and animator for the 800-square-foot Spectacolor sign, the first such billboard on the square. (The lightboard’s manufacturer stated: ‘The computer is the artistic frontier of the next decade’.) Dickson’s primarily worked at night, and did so from an elevated position behind the sign itself. Not only did this allow her to take the aerial photographs of Times Square that would become her source material for years to come, but she was also quick to recognise the potential of this nascent technology – both in terms of technology and visibility. In 1982, she secured funding from the Public Art Fund to initiate ‘Messages to the Public’: an ambitious series of artist commissions from the likes of Alfredo Jaar, Jenny Holzer and Keith Haring that would be conceived for and animated on the board. As Russell Miller summarised for The Blade Toledo: ‘every month, a different artist presents a 30-second animation on the Spectacolor light board—an 800-square-foot array of 8,000 red, white, blue, and green 60-watt bulbs that dominates the Times Square vista.’

These distinctive hues – reds, whites, blues and greens, seen against darkness – were formative for the development of Dickson’s artistic practice. ‘The first key for me finding my voice visually’, the artist notes in a conversation with Odili Donald Odita, ‘was working on a digital light board’: ‘I found myself hypnotized by the potential of color against black’. And, in the many series that followed, Dickson strove to replicate these nocturnal tones, bringing beauty and intrigue to metropolitan scenes that would otherwise be overlooked – and doing so on such devaluated materials as AstroTurf, Tyvek and vinyl. Whether in the crepuscular fluorescence of her New York highways, the garish syntheticism of her Las Vegas casinos or, most directly, the paintings of Times Square, Dickson’s works could be framed as experiments in colour theory, in this sense: how certain tones enhance or alter in response to those around them; how the introduction of an atypical colour can alter our relationship with a particular subject. As Josef Albers once noted, in a manner that feels pertinent to Dickson’s memoirist landscapes, when we study colour, ‘we practice first and mainly a study of ourselves’.

For it should be noted that, when we voyeuristically trespass upon these landscapes, constructed as they are in one and two-point perspective, we are doing so from the viewpoint of the artist herself. (‘I’m not giving you a universal truth’, she states.) And, as such, we are sampling the lived experience of a woman navigating both a stiflingly male space and a suffocating metropolis in which crime, addiction and poverty forces communities into the shadows. In ‘Peepland’ (1992–2017), topless women gyrate for a crowd who leer from beyond the frame; in Times Square, men lurk in the shadowy doorways of strip clubs. Numerous works, from the 1992 series ‘Trust Me’ to today, are marshalled by the heavy silhouettes of police. (‘Male power personified,’ Dickson terms them.) But Dickson’s depictions of (architectural, social, cultural) power structures, of inequality and lingering threat, are not rendered in the name of verisimilitude alone, but as an act of reclamation. ‘I paint things that frighten me’, she notes. ‘I take control of them in paint.’

Indeed, Dickson is drawn to uncertain scenes that embody both negativity and optimism, both fear and its foil. Where there is distance, there is empathy; where there is flatness, there is depth. Where there is darkness, there are the fluorescent light that forces its way through. In rearticulating these urban landscapes in her distinctive style (‘muzzy realism’, Kraus terms it), Dickson does not strive to replicate her source photographs, but to isolate and amplify the experiential magic of these shared spaces. To see beauty where it should not be. To find that which ‘resonates beyond itself’. Speaking of the often-cited connection between Dickson and Edward Hopper, Kraus nods to the way in which the painters ‘use an elusive realism to capture the strange sadness just under the surface of everyday life.’ And, while accurate, it is prescient to note that, in Dickson’s work, everyday life is very keenly alive. There is a nostalgic edge to her panoramas, but it is a nostalgia that connects the past with the present, while pointing optimistically to the future. ‘They are of another time’, Dickson notes, simply, ‘but they’re still here.’